Loneliest Beach In the Megalopolis

WALKING AND DREAMING ON A CITY’S WILD SHORE by David K. Leff

It’s a breezy, cloud-studded summer day on Connecticut’s longest undeveloped and unprotected barrier beach less than an hour’s drive from Manhattan. Smells of salt and desiccating seaweed are strong. From a cramped parking lot at the east end of Long Beach West in Stratford, I follow a sandy path over dunes toward Bridgeport’s Pleasure Beach along the slender handle of this garden-spade-shaped peninsula with its wide blade aimed at the harbor of Connecticut’s largest city. Long Island Sound sparkles on the south with wrinkle after wrinkle of wind-driven waves. To the north, tidal flats edge a narrow inlet known as Lewis Gut where great egrets are wading. Beyond is the bright green marsh of the Stewart B. McKinney National Wildlife Refuge, a place known for clapper rails and busy with salt marsh sparrows during migration. The same glance holds houses, boxy industrial buildings, and fuel storage tanks that stretch along the mainland toward the rectangular geometry of Bridgeport’s skyline.

Situated opposite the state’s densely settled coastline, the two-mile-long, eighty-acre beach once boasted a lively summer community and an amusement park luring tens of thousands of visitors on warm weekends. Now it’s an isolated, quiet stretch of shore, home to threatened piping plovers and least terns. Horseshoe crabs and diamondback terrapins nest in its sands. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service once eyed the land for the refuge, while a nearby urban community has long sought swimming and active recreation.

From the crest of thickly vegetated dunes I spot families enjoying the beach while a few sunbathers, suits optional, lay barely visible among the sandy hillocks. Invasive spotted knapweed thrives and Rosa rugosa grows in low pink-eyed flower thickets. Mullein stalks stand like candles at the trail’s edge and American oystercatchers sail overhead. String fences mark tern and plover nest sites.

Intoxicated with spicy sea smell and rhythmic surf, I reach a stretch of cracked, weed-wracked pavement. Until a couple years ago, it ran between forty or so abandoned cottages that some called Connecticut’s largest ghost town. When I grew up nearby in the 1960s, this was a vibrant blue collar getaway busy with bicycling children and fragrantly barbecuing fish caught in the surf. But built on municipal property rented for decades at a bargain, leases weren’t renewed after emergency response and public use concerns were raised in the 1990s following a protracted and rancorous debate.

When I was last there a few years ago, the derelict cottages were still standing. Not a sheet of glass remained intact and the street sparkled with prismatic fragments. Names and obscenities were spray painted across shingles and clapboards, and furniture, clothing, mattresses, and magazines were strewn about as if tossed by a hurricane. Several cottages had burned and metal pipe and wire, rusted bright orange with salt air, seemed to glow among the ashes and charred remains.

Today there is little evidence of these homes following demolition and beach restoration funded by a federal grant. A couple orioles flit past me and I hear the sharp calls of catbirds and mockingbirds above the surf. Clumps of fleshy prickly pear cactus, a Connecticut special concern species, grow at the macadam’s broken edge.

Soon I pass a rusting fence and enter Bridgeport’s Pleasure Beach in an area of grasses, wildflowers, and broken pavement where about 500 cars once parked during amusement park days. Now it’s an osprey paradise with several nesting pairs, often on abandoned utility poles. One of the large black and white raptors flies low over the water as I walk toward the graceful twin truss towers of WICC radio where yet another nest is wedged in the metal fretwork. Poking the sky like ersatz Eiffels, the transmitters remain the last active human presence here.

Carefully stepping on buckled macadam along a broken stone wall at the edge of Lewis Gut and looking out at a grassland dotted with beach plum, I watch downy woodpeckers, mourning doves, a flicker, and a lone hummingbird. A hundred species can be spotted here on a September day says Patrick Comins, Audubon Connecticut’s Director of Bird Conservation.

Collapsed debris from the bumper car building sits vacant beside clustered trees. Further distant stands a mound of ruins that was the carousel building featuring a finial-topped circus-tent-style roof. Years ago the amusement park’s beating musical heart, it’s a mere hulk, a desolate pile of shingles, fractured and weathered lumber, wire, and pipe. Beyond it lurks the rounded concrete block shell of Polka Dot Playhouse, once an amateur theater where my mother performed.

Soon I come to the dilapidated wooden bridge that used to connected Pleasure Beach to the crowded streets of Bridgeport’s East End, little more than a baseball’s throw away. The planks are littered with gull-dropped oyster shells and the metal truss swing section in the middle is locked in the open position. About 150 feet of missing deck, burned in a 1996 fire, reveals charred timbers beneath. The blaze left the already decrepit bridge unusable, stranding scores of people and over 150 cars that were ferried to the mainland, including Polka Dot’s cast for Neil Simon’s “Laughter on the 23rd Floor.” With access now only by boat or the long walk I’d just taken from Stratford, Pleasure Beach fell into a deep isolation while remaining tantalizingly close to thousands.

Containing 20% of Connecticut’s undeveloped barrier beach, this sandy, windswept land seems deceptively pristine with dunes, tidal wetlands, and sand flats. An Audubon “Important Bird Area,” it not only hosts threatened plovers and terns, but offers wintering habitat for waterfowl, songbirds, and raptors, and a critical stopover for thousands of migratory birds, according to Audubon Connecticut executive director Tom Baptist. “With so much wildness so close to so many people,” Baptist muses wistfully, “the area is a conservationist’s dream.”

Pleasure Beach has always been the stuff of dreams. Rumored to harbor Captain Kidd’s buried treasure, in 1892 it was transformed into an amusement park with a carousel, restaurant, theater, and ball fields. By 1905, advertisements boasted 100 attractions including a ballroom with 2,500 incandescent lights. A few years later the park’s owners erected a $65,000 bridge so patrons could “come and go without any delay.”

Bridgeport purchased Pleasure Beach in 1919. It was popular for decades, especially among factory workers in a city described by the 1937 WPA guide to Connecticut as having “more diversified industries” than any other in the country. At its height in the mid-twentieth century, the park featured a covered midway including a shooting gallery, funhouse, penny arcade, photo studio, and guess-your-age game. There was an open-air arena, convention hall, swimming pool, miniature golf course, and a ballroom with high arching beams, a polished hardwood floor, and revolving crystal lights. Big bands like Benny Goodman, Gene Krupa, and Glenn Miller attracted gleeful dancers. Besides the carousel, rides included a large wooden roller coaster, speed boats, a mini railroad, flying scooters, and the old mill with its momentary darkness for lovers. The park was alive with colored lights, schmaltzy music, the scent of frying foods, the patter of barkers, and children laughing.

By the 1960s, years of financial woes, devastating fires, and political infighting took their toll. The amusement park closed, many rides were dismantled, and the area was left to picnickers, beachcombers, and Polka Dot Playhouse ticket holders. I remember wandering the abandoned midway in those years while my mother rehearsed, finding my way into the carousel building where the strangely still horses swam in shafts of light alive with dust motes. Trying various mounts, I’d dream of joining John Wayne’s posse or of riding in a royal fox hunt.

I was not alone in my Pleasure Beach dreams. The park’s closure induced visions for a hotel and conference center, a Disney “regional entertainment” venue, a Donald Trump world-class theme park, luxury condos, a maritime “Amazement Park,” a casino, an aquarium with a nightclub and shops, and a nudist camp. All became mirages because Pleasure Beach dreamers always awaken to the hard reality of a replacement bridge costing $20 to $30 million. The issue has proven as difficult as crossing the damaged structure.

The bridge has always cast a spell. Those who once traveled its rough planks have indelible recollections of a bumpy, clickety-clack ride. It’s the first boyhood Pleasure Beach memory of Bridgeport State Representative Don Clemons who recalls getting halfway across the span and also hearing the upward clicking of the roller coaster, a brief silence, and then the screams of riders as they plunged downward. A former firefighter, he was on duty at a nearby station during the fateful blaze. Clemons knows that fond memories aside, deciding Pleasure Beach’s future will require sturdy metaphorical bridges among many stakeholders.

From the bridge, I walk toward the beach with a view west across the slate gray water of Bridgeport harbor with its boxy power plant and tall stacks. Soon, I come to a broad, modern paved road leading from a desolate and vandalized concession stand of decorative concrete block known as the Harbor Hut to a spacious parking lot fronting on a long, low bathhouse pavilion of the same material which stands forsaken at the edge of the dunes. Built shortly before the bridge burned, I imagine it as a giant tombstone marking the last grand dream of public access for ordinary people. I walk through the structure’s high central arch and down a broken boardwalk to where waves are pounding the sand.

The wrack line and water’s edge are littered with seaweed, oyster, quahog, razor clam and mussel shells, horseshoe crab carapaces, and lobster parts along with some chunks of lumber, rope, plastic shards, and bottles. Feeling waves pound in my chest and gulping the briny air, it seems a minor miracle that on a warm, sun-washed day I could walk over a mile without seeing a soul on a beach in one of the most thickly settled places in America. Finding nature resurgent in an area long subject to intense development and redevelopment was heartening. But the ghostly Pavilion behind me was a reminder of the sweating thousands living along Bridgeport’s densely packed streets eager for a day in the sun and sand. Feeling conflicted, I sought out some of the many people who care deeply about this place, but found their opinions as strong and polarizing as the tides.

Not long ago, I remember the late George “Doc” Gunther, a retired naturopath who served a record four decades as Stratford’s state senator, recalling the gloss and glitter of the midway and ballroom, summer dreams of the “greatest generation.” An early conservationist, in 1964 he helped plant beach grass on the dunes, but also advocated rebuilding the bridge. Gunther ran a hand through his trademark flattop haircut while imagining a future with swimming, fishing, picnicking, a concession stand, an environmental education center, and perhaps a fine restaurant. Sympathetic to the plight of plovers and terns, he worried that the birds’ revival might restrict access to the state’s “finest bathing beach.”

“It’s a big beach,” says the Fish and Wildlife Service’s Andrew French, and he doubts endangered birds could ever prevent public uses. While agreeing that swimming, fishing, walking, and similar activities can be compatible, he’s concerned that basketball courts, concession stands, ball fields, and the like might not be the fragile barrier beach’s best use.

Easy access to Pleasure Beach is the rightful heritage of Bridgeport’s East End according to many in this densely urban minority community served by one small park. On a hot, humid August day a couple of years ago, I visited East End Community Council members in the group’s crowded storefront office a few blocks from Pleasure Beach’s cooling, unreachable breezes. Despite a consensus that the park was big enough for both people and birds, those gathered left no doubt that people came first, and a few in the room echoed man’s biblical grant of dominion over animals. “Our kids should be able to walk the shore, pick up shells, and experience nature,” asserted the Council’s Ted Meekins, a retired Bridgeport policeman. Water taxis might serve temporarily, but the group believed a bridge would provide the most convenient, year-round access.

Conservation efforts began in earnest when the cottage leases were not renewed following burning of the bridge and rocketed forward when The Trust for Public Land, a private non-profit land preservation group, and the town of Stratford signed a complex option agreement in 2008 to ultimately sell Long Beach West to the Fish and Wildlife Service. But the deal collapsed in a tangle of appraisals, fundraising, and thorny politics. Although the cottages are now gone, the long-term fate of Stratford’s portion of the area remains uncertain. A municipal task force proposed a boardwalk, bathrooms, and other amenities not long ago, but with increasingly damaging storms and difficult funding and permitting issues, such dreams, like many before it, may remain unrequited.

Walking back to the bridge with a freshened breeze in my face, I wonder about the fate of Bridgeport’s 2012 Pleasure Beach Master Plan, the latest vision for this place where plans are as protean as the constantly shifting barrier beach landscape. It’s reassuring to at last have a vision seeking a balance that “will allow visitors to the park and endangered and special plant and wildlife species to co-exist.” The colorful, well-written document ultimately calls for trails, a playground, a nature center, community gardens, soccer and softball fields, tennis and basketball courts, as well as surfside fishing, swimming, and other uses and improvements.

Access by water taxi is anticipated by late 2013 and work on rebuilding the pier, harbor hut, and pavilion is expected to begin by then. Given the history of this land which still seems to maintain an air of amusement park illusion, it’s hard not to be agnostic on the outcome. Audubon Connecticut is trying to ensure that the right balance is found between humans and nature by developing a corps of “wildlife guards,” trained high school students who will monitor the site and educate visitors.

Standing on the photogenic, but desolate umbilical bridge and gazing across the waves at the city’s huddled houses and large industrial structures, I mull over the various proposals. The breeze picks up and I feel like Fitzgerald’s Gatsby staring over the rippled waters of Long Island Sound to Daisy’s dock with an unfulfilled dream that “must have seemed so close that he could hardly fail to grasp it.” Certainly, without building bridges among people, dreams for Pleasure Beach will continue just beyond reach and its isolation will remain both a blessing and a conundrum. In the short term, at least, time and tide are on the side of the birds and those seeking a solitary seaside walk in the heart of sprawl.

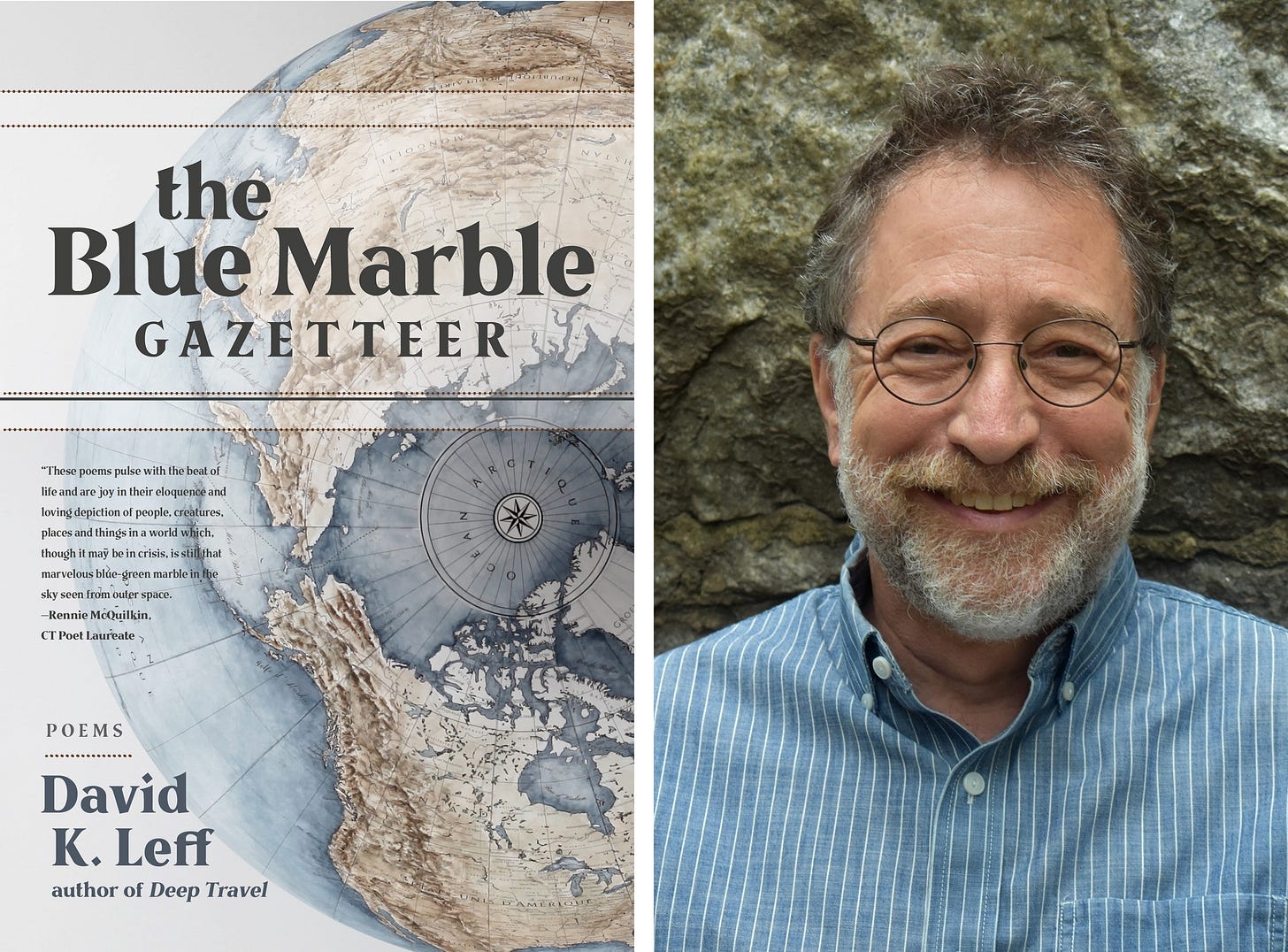

David K. Leff is an award-winning poet and essayist, and former deputy commissioner of the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection. He is the Canton, Connecticut poet laureate, deputy town historian, and town meeting moderator. He was a volunteer firefighter for 26 years.

From the Wayfarer Archive, 2012