In Search of Elliott’s Cabin

by Dustin Grinnell

In the picture-perfect village of Lauterbrunnen, Switzerland, I went looking for an old friend’s cabin. I didn’t find his home, but I found what he left behind.

Situated at the foot of the Alps, Montreux, Switzerland, is filled with cultural and historical pleasures: a hilltop Old Town; Switzerland’s oldest castle, the Château de Chillon; and a nine-foot-tall statue of Queen’s lead singer, Freddie Mercury, to name a few.

Montreux was my third stop on an eight-day trip around Switzerland, a chance for me to relax before starting a new job. There was so much to see, but I wanted to keep moving. However, I was torn on where to go next: Interlaken or Grindelwald. Both looked charming, with spectacular views of high peaks and epic glaciers.

I was walking along the shore of serene Lake Geneva, trying to decide, when my phone beeped with a notification from Facebook. An old college friend, Elliott “Eli” Mazzola, had commented on my photographs of Zermatt, a small mountain village in southern Switzerland with dramatic views of the Matterhorn, a majestic pyramid of jagged rock and snow.

He wrote that he was envious of my trip around Switzerland, especially since he’d recently found himself in New Hampshire after years of travel that had included a summer of work and play in Lauterbrunnen, Switzerland. He suggested I visit the village, which, according to my Lonely Planet guidebook, was “postcard perfect” and “nestled deep in the valley of seventy-two waterfalls.” Apparently, it was also a magnet for BASE jumpers, which piqued my curiosity as a lover of extreme sports. Since the village was in the Jungfrau region—coincidently about halfway between Interlaken and Grindelwald—I decided to drive there next.

I was surprised, though, that Elliott might be jealous of my travels. I had admired and envied his world travels since we graduated from Wheaton College in Massachusetts in the late 2000s. I’m no stranger to international travel—having backpacked through over fifteen countries in the past fifteen years and even ridden a motorcycle across the United States in 2015—but Elliott’s expeditions were on a whole other level.

He’d spent the last decade wandering through far-flung regions with just his backpack, camera, and unlimited wanderlust. He’d spent six months traveling across Eurasia by train, four months hiking across the Alps, and two months hiking along the GR10 in the Pyrenees, and he had embarked on countless treks, road trips, and hitchhiking adventures with friends and family. Over the years, he would post pictures of his adventures on Facebook, and they never failed to dazzle me. Whether he was riding rails to Ho Chi Minh City in Vietnam, hiking in the Pyrenees, or remodeling a hut in the French Alps, Elliott’s journeys seemed almost fantastical, especially since I was admiring them on computer screens in Boston offices.

For years, Elliott has reminded me of Christopher McCandless, an American adventurer who was the subject of the book and movie Into the Wild. Like McCandless, Elliott is free-spirited, rebellious, and nomadic, but also kind, generous, and sensitive. Indeed, he’s branded himself a “modern pilgrim” on his website. In college, he forged his own path. A philosophy major with a minor in math, he liked to play the organ in our college’s church, sometimes late at night.

Elliott was three years behind me in college, so we didn’t run in the same circles, but we both played rugby and rubbed shoulders at drink-ups after games. I recall him as friendly, funny, and often intense. His personality exhibited a wild, extreme edge, and his eyes seemed fiery and enigmatic. At rugby parties, there was no dare he would turn down. Once, he tried to pole-vault onto the roof of a friend’s house and crash-landed with such force, I thought he might never walk again, let alone compete in a rugby match.

It didn’t surprise me that in adulthood, Elliott spent his twenties and thirties rebelling against the conventional values of society while satisfying his curiosity and lust for adventure.

While I was in Switzerland, Elliott was enjoying a nearly seven-hundred-mile hike in New Hampshire, piecing together different trails to create two long unofficial trails that stretched from the southwestern corner of the state, where it meets Massachusetts and Vermont, all the way to the northeastern corner near Mont d’Urban, where it meets Canada and Maine.

Occasionally, he’d post highlights on his Facebook feed, such as the time he’d missed a turn, walking three miles in the wrong direction, and knocked on someone’s door in a rural part of the state to ask for directions. The inhabitants of the house invited Elliott in for snacks and cocktails. Later, they took him to the county fair and gave him a bed for the night. The next night, they gave him a job dropping garlic cloves into bottles of salad dressing on an assembly line. He made $400 that night, enough to pay for his entire hike to Canada.

How Elliott found himself in Switzerland years earlier had been something of an accident. At the time, he’d been living in a wooded part of France in a makeshift hut that he’d remodeled with a friend. He was traveling when he received news that the city was knocking down his hut. Already on a road trip in Europe, Elliott didn’t complain to the city. Instead, he kept going and eventually landed in Lauterbrunnen. While strolling through the woods in Winteregg, a small alpine village directly above Lauterbrunnen, he stumbled on a vacant cabin with panoramic views of the snow-capped mountains.

I could live here, he thought, and from early May to late August, he did just that.

Elliott’s cabin was about thirty feet long and ten feet wide. The roof was rotten and riddled with leaks. Spiders and mice were his companions. He placed boards in the cabin’s rafters for his bed, allowing him to fall asleep and wake up to striking views of Jungfrau, one of the main summits of the Bernese Alps.

Without electricity or heat, he relied on a firepit outside to keep warm, while a nearby spring provided fresh drinking water and refrigeration for cold foodstuffs like beer and milk, which he hid under a footbridge. Other foods he would gather directly from the wild, like fresh-picked wild berries and chanterelles.

For money, Elliott worked at Horner Pub, a small bar in Lauterbrunnen. Every morning, he’d walk ten minutes down a path, strap a parachute to his back, and leap off a two-thousand-foot cliff to start his shift. After work, he’d take the cable car up the mountain to Winteregg and make his way back to the cabin.

For the most part, Elliott lived alone, but his friend Sandra joined him for a few days at a time whenever she visited Lauterbrunnen to BASE jump. Elliott also wrote letters to his companion Vic, telling him of the new home he’d found and all the fine places Vic could set up his easel and paint landscapes. Vic joined Elliott in July and stayed until they both left in August.

The cabin wasn’t far from some of Switzerland’s most popular BASE-jumping locations, including the iconic Nose launch site, which has garnered a reputation as one of the most challenging and breathtaking BASE-jumping spots in the world. Thrill seekers and adventurers come from around the globe to experience the rush of leaping from the perch high above the valley floor and soaring over the Swiss Alps.

Elliott was new to the sport of BASE jumping, but he racked up nearly two hundred jumps during his stay in Switzerland. He also worked on perfecting his photography, and between the scenery and the extreme athletes, he was never short on subjects.

Years ago, he held an art exhibit in New Hampshire showcasing his adventures, including his time in Switzerland documenting the BASE jumps he and his friends had taken. I’d been a city dweller for many years, spending my weekdays cooped up in offices, so I gladly took advantage of the opportunity to learn more about Elliott’s lifestyle, which felt risky and just plain badass.

One piece at the exhibit stood out to me: a framed photograph of a person flying through the sky in a bright-red wingsuit, the Swiss Alps in black-and-white providing a dramatic backdrop. I paused in front of the photograph for several minutes, overwhelmed by a mixture of awe and dread. What an incredible sense of freedom it must have provided, to slice through the mountain air like a bird. What a profound feeling of being alive, to cheat death as this BASE jumper had.

It was that photograph, I think, that piqued my interest in Switzerland. However, it was my fascination with the extreme rewards of this dangerous sport that led me to search for Elliott’s cabin. I may have told myself the cabin could be a quiet place to chill for a while, but in a way I didn’t fully understand, seeking it out was a meaningful adventure.

A cabin in the woods, as cliché as it may seem, represents sacred space in my mind. I’ve always admired Henry David Thoreau and his experiment of living in a small cabin on Walden Pond. I also grew up in a small house in the woods of northern New Hampshire and often imagine I’ll grow old in another. At the same time, I’ve always glamorized and romanticized the lives of explorers, adventures, and nomads—people like McCandless and Elliott, who live at the edges of society. I often treat their lives as fantasy while stubbornly ignoring the difficult realities of living.

Tracking down an old friend’s lost cabin was a romantic, if not quixotic, goal, but Switzerland seemed like the place for that kind of thing. It was where romantic writers like Goethe, Lord Byron, and Hermann Hesse produced some of their most famous works. The country was also one of the spiritual homes of my favorite school of thought, existential philosophy. I’d already planned Friedrich Nietzsche’s home as my last stop.

I drove an hour and a half from Montreux to Lauterbrunnen. As I got closer to town, I was awed by the scenery all around me. Streams and rivers cut through lush wildness, and the towering alpine peaks made for a dramatic backdrop. The Eiger, Mönch, and Jungfrau mountains, part of the Bernese Oberland range, dominated the skyline. Driving through the village, I passed chalet-style lodgings and walkways jammed with tourists in outdoor gear. I gazed up at gigantic cliffs to admire the view of water from the wispy Staubbach Falls disappearing into the air above the valley.

Elliott hadn’t yet responded to my message for more specific directions to the cabin, so all I knew from his original Facebook comment was that I should take the cable car from Lauterbrunnen up to Winteregg and “follow the base jumpers.” I asked a few staff members at a restaurant if they knew where I could find the cabin, showing them Elliott’s photo on my phone. They didn’t know, but they directed me to his former employer, Horner Pub, a popular hangout for BASE jumpers. I popped into the bar after lunch, but it was mostly empty, so I decided to circle back when I got back to town.

The cable car ascended toward Grütschalp, offering spectacular views of snow-capped mountains. At the top, I boarded a train that ran along the horizontal edge, providing beautiful views of the Eiger, Mönch, and Jungfrau. Every new vista had me lunging for my camera. Deciding to give Elliott time to respond with directions, I took the train to the last stop, Mürren, and strolled through the mountain village.

An hour later, I got back on the train and returned to Winteregg. Elliott still hadn’t messaged me, and I hadn’t seen anyone who looked like a BASE jumper on the train, so I followed the main trail toward Mürren using the photograph of the cabin for guidance by holding my phone up against the mountains. Twenty minutes into the walk, it started raining. Feeling I’d gone too far, I turned around, effectively giving up on my search.

I was heading back to the cable car when Elliott finally responded. To my delight, he’d sent a pin with the coordinates of the cabin’s location. The pin led to a trail that would take me to the cabin. It was about a thirty-minute walk in the same direction I’d been walking. I was glad to have concrete directions, but I had to move fast, as it was 4:15 PM and the last cable car back to Lauterbrunnen left at 5 PM.

When I reached the pin’s location, I took a left onto a smaller trail that circled down past wooden buildings, though none exactly resembled Elliott’s home. I continued ambling along the trail, passing more structures, empty dirt lots, and rock piles. Finally, I reached a dead end surrounded by huge piles of rocks.

The cabin wasn’t there.

As I doubled back, I realized that some of the empty lots looked suspiciously like the location where Elliott’s cabin had been. Had another one of his homes been demolished? I took photos of the area, including the empty lots, and sent them to him.

Forty-five minutes later, I’d taken a seat at the bar in Horner Pub. I ordered a German beer and, checking my phone, saw that Elliott had responded to my messages. He admitted his coordinates had led me to the wrong location, and provided more specific directions that would’ve been a short walk into the woods from the Winteregg stop.

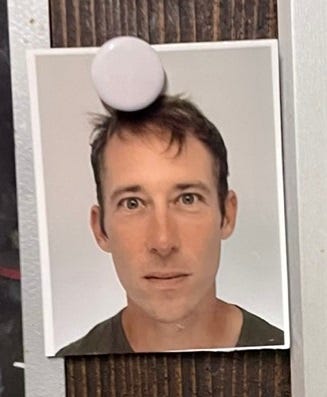

I was getting ready to leave when I spotted Elliott’s headshot tacked to the wall behind the bartender. Staring, I was taken aback by the fierce, almost anxious expression Elliott wore. I wondered what had been going through his mind when the picture was taken. Had Elliott’s travels and BASE-jumping hobby, though exciting and life-affirming, made him feel frayed, nervous, and sometimes lost due to the uncertainty and risks involved? Did his face exhibit the “price” of living a nomadic lifestyle?

With the bartender’s permission, I took a photo of the picture. Once I had, I asked the bartender if she’d ever met Elliott, but she was new to the area and wasn’t well-connected with the BASE-jumping community. Wondering if any BASE jumpers were present, I scanned the room.

Behind me, a man sat by himself at a large, round table, drinking beer. He was facing a wall covered with photographs of BASE jumpers who, the bartender explained, had died while performing their sport in the region. Was he paying homage to a fallen comrade? Or perhaps he wasn’t a BASE jumper and had chosen the table at random, hoping to enjoy some time alone with his thoughts. Either way, I didn’t feel like disrupting him, so I finished my drink and left the pub.

I was planning to stay the night in Wengen, a car-free village twenty minutes away by train, so I stopped by a café for a coffee. As I waited in line to order, I looked to my right and spotted a framed photograph of a person slicing through the air in a bright-red wingsuit. It was the photograph that had captured my imagination at Elliott’s exhibit in New Hampshire and had led me to this small mountain village.

I booked a hotel using my phone and grabbed a seat on the train to Wengen. Looking out the window at a new vantage point of Lauterbrunnen, I thought about Elliott and the cabin I couldn’t find. I was grateful he’d commented on my post; without it, I would’ve missed the majestic village. And while I didn’t find Elliott’s cabin, I found where he had worked and lived and the images he’d left behind.

Enjoying the scenery, I wondered why an old college friend had such a hold on me after all this time. I’ve traveled widely and had my fair share of adventures, but the bulk of my adult life hasn’t been that exciting or interesting. It involves holding down a day job, staying rooted to an apartment, and relishing my daily rhythms. Elliott lives spontaneously, bouncing from gig to gig, dwelling wherever he lands, ducking routines and monotony. Since my first job out of college, I’ve been paying my bills with money from “The Man”; Elliott, on the other hand, has spent that time giving him the finger.

I think Elliott’s life represents wish fulfillment for me, as I wish I had the guts to live like him—to go wherever I please, make art out of what I see, and unapologetically avoid the common obligations and responsibilities of adulthood.

When I returned to Boston a week later, I was curious about where Elliott was on his trip through New Hampshire. Checking Facebook, I saw that he had just shared updates about his journey. He’d posted pictures of everything from mountains to mushrooms. I scrolled through the photos of him strolling in the forest along dirt paths, sometimes straying off the trail. He played the organ for strangers in a local church and swam naked in a secluded pond with beavers, making fun of trespassing laws. He camped wherever he liked and slept in his tent under the stars.

Given how much I idolize Elliott’s life, I often ask myself why I don’t strike off in a similar fashion. I’m not married, I don’t have children, and I now work remotely. Yet as much as I admire Elliott’s free-spiritedness, wanderlust, and artistic choices, his lifestyle isn’t a dynamic that would work for me. I like a certain level of security, perhaps because I didn’t have it in my early life. My daily routines help me write productively, and I fear that without them, my days would sprawl together and my output dwindle.

I’m also curious about Elliott’s motivations in the same way I’ve always been fascinated about Christopher McCandless, who ultimately died in the Alaskan wilderness. Some people idealize McCandless for being the ultimate explorer, while others criticize him for being reckless—entering the outdoors unprepared and dying because of it. McCandless inspires me, but it’s clear he had his demons. He seemed traumatized by his complicated past. The movie Into the Wild captured the emotional wounds that animated his travels—family dysfunction that he seemed unable to confront.

I still have the photo of Elliott’s picture tacked to the wall of Horner Pub on my computer. Whenever I look at it, I think of McCandless, who seemed driven by equal parts bravery and anxiety. McCandless was clearly running toward a vision for life that was hard to define, much less achieve—an authentic way of living that only a romantic could imagine. But he was also running away from something. Was Elliott running too?

Looking at Elliott’s picture, I wonder if what I see in his eyes is not only the anxiety of an uncertain and risky lifestyle but a kind of terror. It takes a rare, brave soul to revolt against the norms of society and go their own way. Maybe Elliott’s expression shows the dramatic gaze of a free man with all the fear of being responsible for his life.

Whatever the case may be, I’ll continue to follow Elliott wherever he goes. And while I couldn’t find his cabin, perhaps I can find a way to balance practicality and romanticism by seeking my own.

Elliott performing a BASE jump from La Mousse in Lauterbrunnen. Video by Roch Malnuit (2017).

Dustin Grinnell is a writer based in Boston. He’s the author of The Healing Book (Finishing Line Press), The Empathy Academy (Atmosphere Press), The Velvet Ghetto (Blue Cubicle Press), and host of the podcast, Curiously. As a travel writer, his stories and articles have appeared in a variety of journals and magazines, including the travel sections of the Boston Globe, the Philadelphia Inquirer, and the Washington Post. He’s won two Solas Awards for Best Travel Writing and received an honorable mention from the North American Travel Journalists Association Travel Media Awards Competition. In 2023, Dustin brought his essays together in a book, Lost & Found: Reflections on Travel, Career, Love and Family, a collection of 25 essays in which he writes about discovering amazing places—and bit by bit, himself. Learn more about his work on his website, and follow him on Instagram @dustin.grinnell and X @DustinGrinnell.